From “The Mustard Seed Garden” to Personal “Fiction” – Bi Rongrong’s Writing about “Truth”

text by Jiang Jun, translated by Wu Chenyun

从“芥子园”到个体的“小说”——毕蓉蓉关于“真”的书写

文:姜俊,翻译:邬晨云

2016.12

Exhibition link: Fiction Landscape,

展览链接:小说景观

Fiction Landscape, Bi Rongrong’s solo exhibition, was unveiled at A Thousand Plateaus Art Space on December 17, 2016. Featuring an array of different media, Fiction Landscape comprised three major parts: weaving, painting and installation. Why would the artist call it “fiction”? Jiang Jun, guest contributor of art.ifeng who is also a young artist and critic, led us to explore further into the exhibition from the perspectives of module and the narrative of “truth”.

2016年12月17日下午3点,毕蓉蓉个展“小说景观” 在千高原艺术空间揭幕。“小说景观”是由不同媒介相互关联组成的整体,主要由编织,绘画,以及装置三部分构成。为什么艺术家把它称为小说呢?“凤凰艺术”特约撰稿人,青年艺术家及艺术评论家姜俊将为大家从模块和“真理”叙述的角度谈谈这个展览。

Installation view of “Fiction Landscape”

A Thousand Plateaus Art Space, 2016.12.17-2017.02.28

展览《小说景观》的现场

千高原艺术空间,2016, 12, 17—2017, 02, 28

(中文阅读请向下滑动)

Bi Rongrong was the first artist I ever wrote about and during the years I’ve witnessed her development from delving into the language of form to the in-depth exploration and question into modules and meaning. Her work could be seen as a mirror of her inner self, radiating genuinely personal narrative. To put it in other words, it could be seen as her autobiographical novel.

I interviewed her during her last exhibition Absolute and we talked about the Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, which is a printed manual of Chinese painting compiled during early-Qing Dynasty. The five-volume manual gives extensive description of the various painting principles and techniques of Chinese painting, including the landscape painting, painting of trees, hills, stones, plum blossoms, orchids, bamboos, chrysanthemums, birds, people and houses. The title derives from Li Yu’s (under whose support that the manual was published) villa in Nanjing which was known as the Mustard Seed Garden. During the past three centuries, the manual has always been hailed as a classic textbook for traditional Chinese painting. It not only deals with general principles and specific paintings skills, but also comprises selected works of great landscape painters, offering a holistic approach for those who want to learn Chinese painting. Lothar Ledderose, German art historian specialized in East Asian arts, described such patterns as modules in Chinese art.

As a trained Chinese painter who then chose to resort to contemporary art, Bi Rongrong’s take on contemporary art is somewhat different and unique compared with her peers. In the Manual of Mustard Seed Garden, a variety of patterns that could be imitated, duplicated and assembled were provided. Similarly, Bi Rongrong comes up with a highly individualized module system during her painting practice. If the Manual of Mustard Seed Garden is a classic standard manual based on the orthodox narrative of literati painting, the modules invented by Bi Rongrong are highly personal and intimate, slowly but continuously generating an interwoven and interconnected allusion system behind the paintings. Each pattern derives from an intimate experience of hers and hence is an imprint of memory. And each work comprises various modules of this kind.

What the Manual of Mustard Seed Garden demonstrates is orthodoxy and authority. It embodies the collective wisdom and experience of painters of different generations. It is a metaphor that has been fixated and a convenient treasure chest for beginners. The correct way to imitate and duplicate is to take today’s context into consideration and then revisit each module. In other words, we need to follow the principles and leave the restrictions behind. It’s of course easier said than done. Most painters, mediocre painters, blindly follow and repeat the fixated patterns, making painting a game of assemblage that is highly abstract and detached from the reality.

Bi Rongrong has a particular liking for painters of the Northern Song Dynasty. Different from painters of the Qing Dynasty, they didn’t have so-called orthodox and universal principles to follow. It is said that Fan Kuan, a Chinese landscape painter of the Northern Song Dynasty, led a hermit life in the untraversed regions in Mount Zhongnan and Mount Taihua. He spent his whole life living within the forests, immersing himself fully in the wind, snow, rain and fog; or in other words, he truly integrated himself with the nature. As a result, his landscape painting brimmed with the flavor of the nature, making viewers feel as if they were surrounded by forests and mountains. According to Fan Kuan, “It’s better to learn from the genuine things than from the patterns set by painters of previous generations. And for me, I would rather follow my heart than the things.” Those great painters traveled around the mountains and rivers to feel the charisma essence of nature with their full heart. And while they delineated the world intuitively, they managed to imbue their own individuality into the images, making the paintings glitter with the charm and wisdom of “truth”.

But Bi Rongrong’s approach is different from painters of the Song Dynasty. Instead of following the principles of the nature, she directly makes use of and appropriates daily life. To some extent, she is like a complier of an encyclopedia of the eighteenth century. But in her case, the “encyclopedia” she complies is all about herself. She once said: “When looking at my work, people may feel they are abstract. Actually that’s not the case. In fact, the way I think of and observe things is under the influence of my training of Chinese painting. In my view, each stroke in Chinese painting represents a slice of things that are figurative. This exhibition could be seen as a continuation of my last solo exhibition in March. Street graffiti, posters and tapestries that I came across during my trips to other cities and countries were my sources of inspiration. I took pictures of them to make them into some kind of archive. Then I detached them from their original context, took some fragments out and enlarge them. The previous exhibitions would give me inspiration for my future work. And as life goes on and as I keep traveling, my practice extends and grows steadily and continuously.” Her work, in essence, is the edited records of the trajectory of her life. It is in this sense that she becomes the writer of her autobiographical novel.

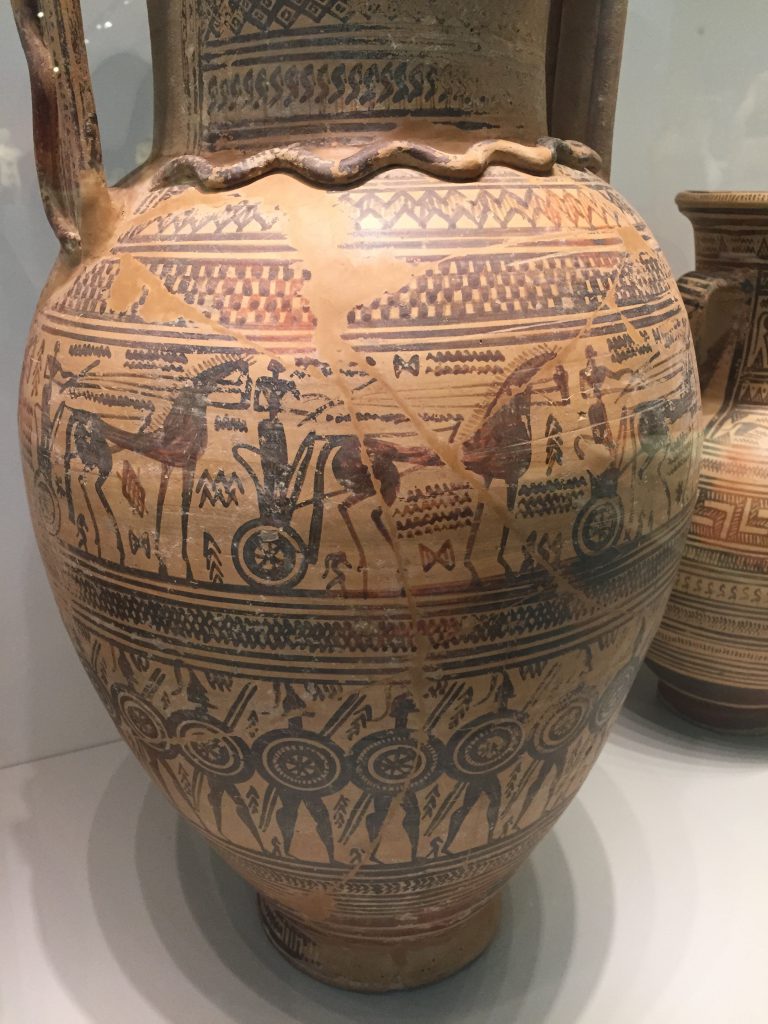

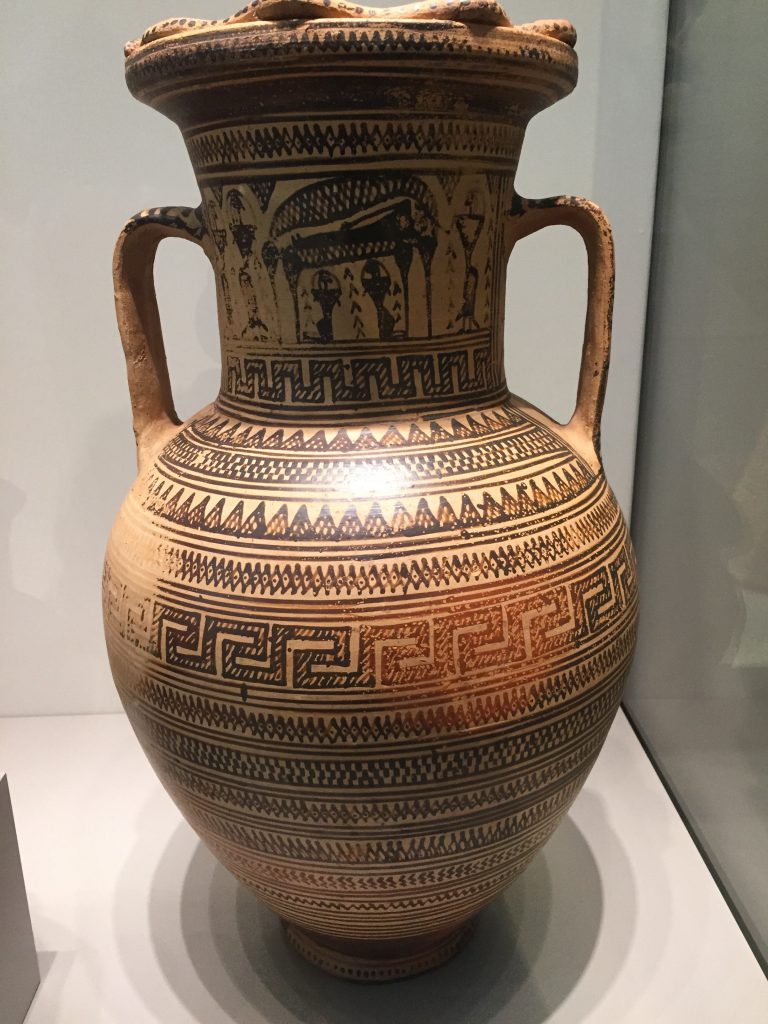

At the moment Bi Rongrong is, quite ambitiously, working on a manual of modules of her own, or say, a private version of the “manual of mustard seed garden”. Each module will be connected with a story or a piece of private memory/experience. For instance, she came across module A during a visit to Pergamon Museum; Module B from the pattern of the stone flooring at the Museum Island in Berlin; Module C, a poster on the street of Manchester; Module D, a poster in Berlin; Module E, slates collected in the Tianyi Pavilion in her hometown Ningbo; and Module F, the brick walls near her studio in Songjiang District… Each of them embodies the moment that she is touched and impressed. More than what they originally stand for, the modules also epitomize the chemistry between the artist and the objects when she first encountered them. Through constant repetition, collaging, rearrangement and overlapping, the new narrative that hereby emerges comprises the somewhat unconscious superposition of memories, and becomes an autobiographical novel.

According to Bi Rongrong: “My practice, in a way, is to create a landscape that I feel and perceive. I try to capture different moments. The process is full of uncertainties, but also contains inevitability.”

Nowadays the so-called universal truth is under serious question, making “truth” an obscure concept. On the one hand, we do not recognize the Manual of Mustard Seed Garden as the sole orthodoxy (a grand narrative of the tradition of painting); and on the other hand, we sniff at various styles of modernism imported from abroad. Basically we live in the post-modernity that advocates the legitimacy of diversity and individuality. Danish philosopher, Søren Aabye Kierkegaard, also known as the “father of existentialism”, proposed two types of “truth” (wahr) in mid-19th century: objective truth and subjective truth, which has given profound inspiration to post-modern philosophers and thinkers. If we suspend the subjectivity of the living people within objective “truth”, it is based on mathematics and science. On the contrary, if objectivity is suspended by subjective “truth”, it is the feelings and perception of the subject that are emphasized. “Truth” doesn’t lie in calculation; and in the context of existentialism, it refers to the interrelation and interplay between the individuals and the world. In the 20th century, Heidegger understood truth as the happening of event (Geschehen). It breaks open fixated concepts and removes concealments, enabling the things that are intricately related to embrace clearing, to achieve the state of “being-in-the-world” (In-der-Welt-Sein). Following the philosophy of Heidegger, Derrida thinks of an open future in which truth symbolizes the possibility to lead the unknown to the future. It comes on the stage one after another, becoming the “truth”, but is under constant re-interpretation and narrative. It is highly personal and private, offering us a landscape of a diverse future.

Artists born in the 80s and 90s, different from their predecessors who were obsessed with grand narrative, are keen on their own stories. Bi Rongrong is one of them. For her, what she attaches more importance to is the subjective “truth” of herself. By meticulously and ingeniously compiling the fragments of memory and feeling together and then visualizing them, she manages to edit them into a novel and landscape of her own. Then she re-opens them with like-minded people, looking forward to a future image brimming with diversities and individualities during the revisit.

毕蓉蓉是我第一个书写的艺术家,我也看着她从一种对于形式语言的探索过渡到对于模块和意义的自我心理机制的追问。她的作品成为了她自我的真实展现,一种本真性的个体叙述从潜意识中涌现出来,就如同自传体小说一般。

记得上次在《穹顶/Absolute》展览的访谈中我们谈到了《芥子园画谱》,那是清朝康熙年间的一部著名画谱,详细介绍了中国画中山水画、梅兰竹菊,以及花鸟虫草的各种绘画技法。其名出自李渔在南京的别墅“芥子园”。300年来《芥子园画谱》都是一部中国传统绘画的经典教材。它从用笔方法到具体景物的笔墨技法,从创作示范再到章法布局,为学习者提供了完整的学习解决方案。德国东亚艺术史家雷德侯把这套中国艺术的范式规定称为模块化的艺术。

而作为国画出生,最后转向当代艺术的毕蓉蓉从一开始就有着不同于一般当代艺术家的视角,如同《芥子园》所提供的各种可以模仿、重复、组合、拼装的图示,她在自己的绘画实践中也思考和制作一套非常个体性的模块体系。如果说《芥子园》是一种基于文人画正统大叙述的经典标准件手册的话,毕蓉蓉的模块就完全非常自我和隐秘,它们逐渐在画面的背后生成一种可以互相引用的典故系统。每一个图示都来自于一段她个人隐秘的经历,是一段回忆的烙印,每一个作品都是由无数个这样的模块构成。

如果《芥子园画谱》彰显的是一套正统性,规范性,是一代代画家们共同的记忆和提炼,是被固化了的隐喻,初学者入门便利的法宝,那么对其正确的模仿和重复就是从当下出发重新开启每一个模块——得意而忘形。要做到这样谈何容易,大部分平庸的画家们都亦步亦趋的重复着给定的模块,使得绘画成为一种脱离现实、抽象组合的变装把戏。

毕蓉蓉更多欣赏北宋时期的画家,因为他们并没有如同清代画家一样有直接可以挪用的一套宣称正统和普世的法则,相传北宋画家范宽隐居至人烟罕至的终南山与太华山,终生以山林为伴,沉浸于风雪雨雾之中,把自我与大自然融为一体,因此他的山水画往往令人仿佛置身于山林中的感觉。范宽认为:“师古人,末若师诸物也,吾与其师诸物,末若师诸心。” 这些大画家们在山川中游历,观察自然,用自己的直观去描绘所见的世界,从而使得个体性融入其中,从内而外展现最为闪闪发光的“真实”。

但毕蓉蓉又不同于宋代大家们,她并非师法山川自然,而是直接从日常生活中抽取、截断,她更像一个18世纪百科全书的编撰者,但一切出于自身。她说:“看我的画面,可能大家会觉得作品是抽象的,其实不然,实际上我的思考方式和观察事物的方式还是受到国画学习的影响,在我看来国画中的每一笔都是具象事物的切片。这次展览是我今年三月份个展的延续,很多素材来自旅途中城市的街头涂鸦,海报,织毯等各种生活周遭的东西。我将它们拍摄下来,成为档案,再抽离,提取和放大。上一次的展览会启发我的下一次创作,随着旅途,生活经历等,一直在延伸和生长。”她的作品其实是关于自我生命轨迹的记录和编辑,她成为了一个自传小说的书写者。

毕蓉蓉正在野心勃勃地制作一本属于自己的模块手册,一本私人秘藏的“芥子园画谱”,每一个模块都配上了相应的故事和一段私人感受的回忆。比如她在一次佩加蒙博物馆(Pergamon Museum)的参观中获得了模块A、柏林美术馆岛的石板地的序列中提取了模块B、在曼切斯特街头海报中抽象出的模块C、从柏林街头的海报生成了模块D、从她的故乡宁波天一阁的石板收藏中导出了模块E、她松江工作室区附近的砖墙模块F…… 它们凝结了一次次的感动和沉思,每个模块不只是有其原来的出处,还有着艺术家和它们邂逅那一刻的化学反应。它们被不断重复、拼贴,再重组、叠加,然后从无意识中涌现出记忆叠加后的新叙述,它们便是每一个自传体小说。

毕蓉蓉对此提及:“我的创作就像是在编一个自己感受到的风景,捕捉各种时刻,这个过程很偶然,也很必然。”

今天传统的单一真理观受到严重的质疑,真理变得模糊不清,我们既不承认《芥子园画谱》为唯一的正统(一套绘画传统上的大叙述),也对于现代主义国际风格嗤之以鼻,我们生活在一个彰显多元个体合法性的后现代中。丹麦存在主义哲学家索伦·奥贝·克尔凯郭尔(Søren Aabye Kierkegaard)在19世纪中期就提出了两种对于“真”(wahr)的范畴,即客观的真理和主观的真理,这深刻的启发着后现代的思想家们。在客观的“真”中,我们把在世间存在之人的主观性悬置,它基于数学和科学;相反主观的“真”把客观悬置,强调存在者之主体的感受。“真”不在于计算性,对于存在主义来说,它是个体的人和世界的关联和互动。之后20世纪的海德格尔认为真理是一种事件的发生(Geschehen),它打开了固化的概念,破除了一切的遮蔽,使得互相链接的万物走向澄明,并在世界中存在(In-der-Welt-Sein)。德里达继承了海德格尔的思路,思考一种开放性的未来,真理就是一种未知的走向未来的可能性,它在不断的重复中出场,成为了“真”,但又不断的被重新诠释和叙述。它非常个体和私人,并提供了我们一种多元未来的图景。

今天80后和90后的艺术家们热衷于自己的故事,他们不同于那些无时不刻都在幻想着庞大叙述的前辈艺术家们。毕蓉蓉便是是其中之一,她更注重作为存在者的我之主观“真理”,她精心地把这些感受的记忆碎片编辑在一起,图像化,串联为一个自己的小说,自己的风景,并和志同道合者一起再次打开它们,在回望中憧憬着个体多元未来的图景。

A

佩加蒙博物馆Pergamon Museum展示的古石墙

Ancient stone walls on display at the Pergamon Museum

Patterns extracted from the pots |纹样的提取

Work |作品

Fiction Landscape – Contour 2 |小说景观-轮廓二

Material: cotton thread|材料:棉线

21.5×14cm

2016

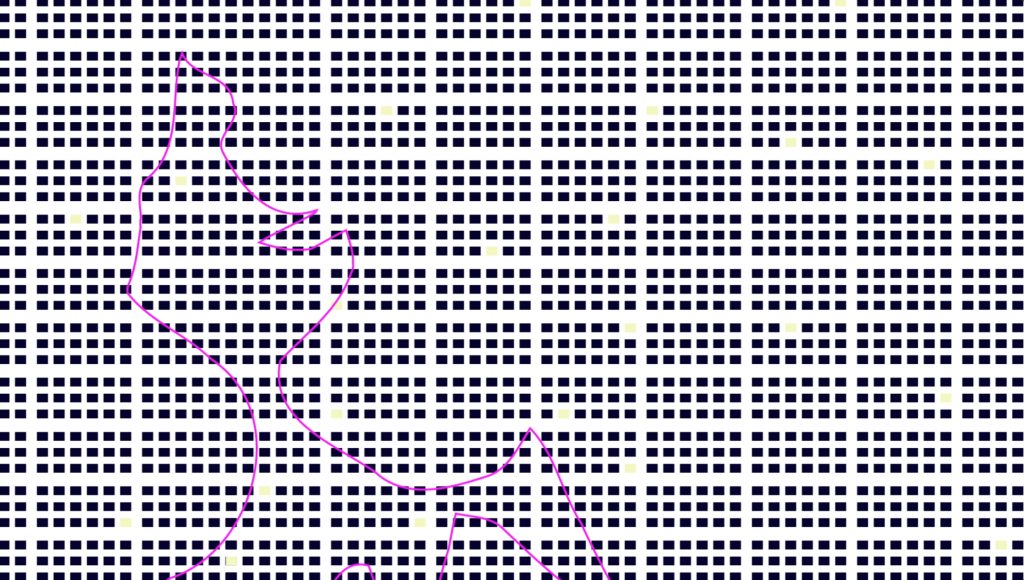

Screenshot of the video Fiction Landscape|小说风景 视频截屏

03‘12“

2016

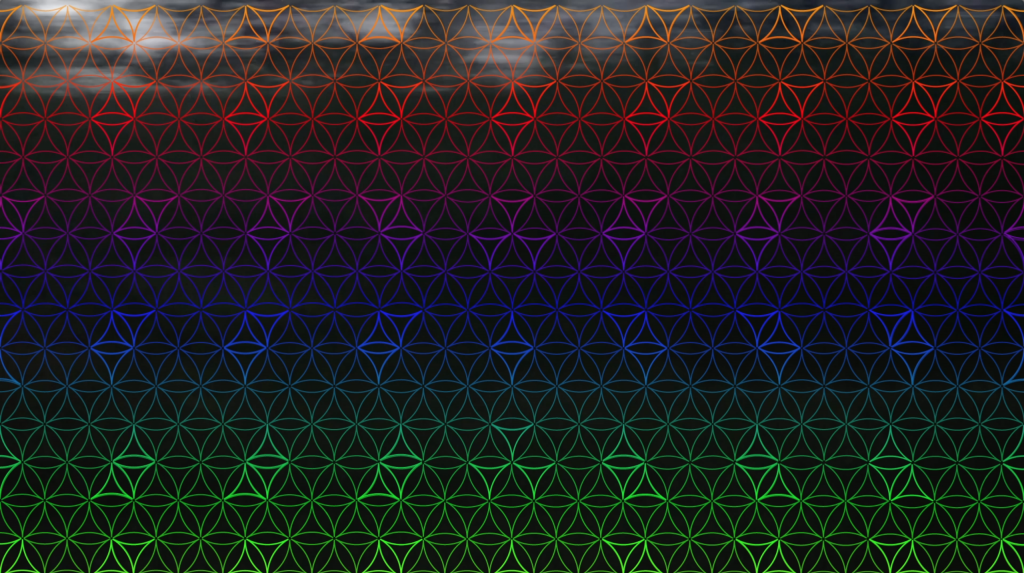

B

Floor of Museum Island in Berlin, Clay pots of ancient Greece (750-720BC)

柏林美术馆岛的地面,公元前750-720之间的古希腊的土罐

Patterns extracted from the pots |纹样的提取

Works |作品

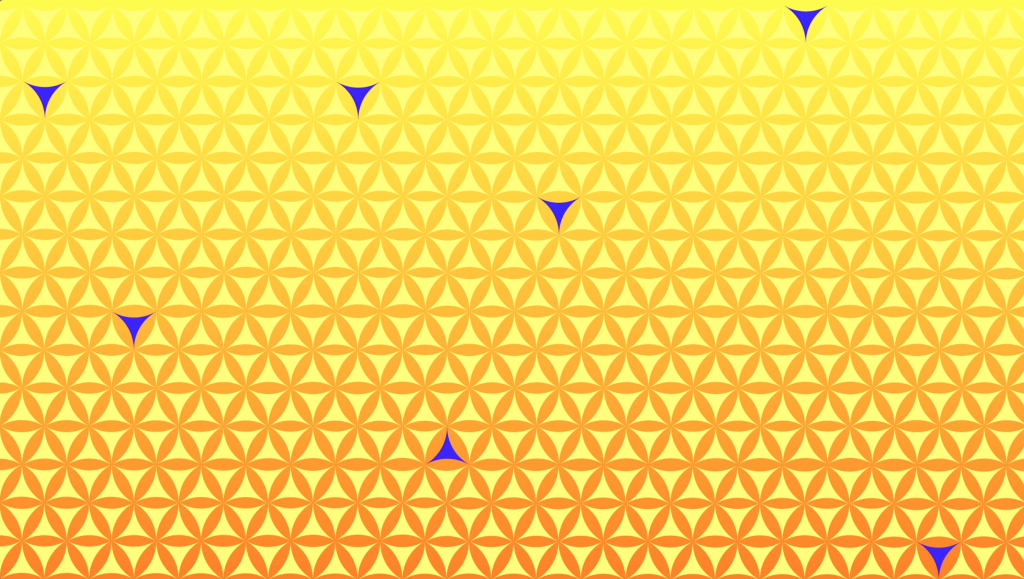

Posters on streets in Manchester|曼城街头的海报

Work |作品

Screenshot of the video Fiction Landscape|视频截屏 小说风景

03:12, 2016

Street paintings and prints in Berlin and Manchester. (I made use of some of the elements in my “Manchester CMYK” series in 2004. This time I continued to draw inspiration from “Manchester CMYK”. During the process of painting, how I choose and extract the elements is purely random and natural.)

E

Patterns being extracted

正在收集的纹样

Antique slates collected in Tianyi Paviliion in Ningbo , brick walls near Bi Rongrong’s studio in Songjiang District, Shanghai

宁波天一阁的古石片收藏; 上海松江工作室附近的砖墙